Point of care ultrasound (POCUS) is being increasingly utilised within acute and critical care environments as an adjunct to the clinical assessment of acutely unwell patients. With the advent of novel training pathways for focused ultrasound Junior Doctors may acquire these skills in a supervised environment significantly earlier in training. Typically training starts as a registrar but I was fortunate to begin ultrasound training during core training (CT) years – a skill that is rare to find at that level. My ultrasound training began with a Royal College of Emergency Medicine (RCEM) Core Ultrasound course undertaken during Foundation Year 2. Subsequent placements within Intensive Care and the Emergency Department enabled completion of the RCEM Core requirements within an eight month period. These locations were ideal for accumulating scans for a logbook due to ultrasound machines being readily available and accessible. Nevertheless, additional supervised sessions from mentors in my own time provided essential ‘real-time’ feedback and practical advice to improve scanning technique. I subsequently continued scanning on the Acute Medical Unit and completed CUSIC, FICE and Thoracic Level 1 within a 7 month period. My experience and usage of USS at the front door has not only empowered me with provision of skills to guide diagnosis, either refuting or confirming, but most importantly provided me with confidence in my own clinical skills and management plans. I see the USS as an extension to my examination.

There are ongoing concerns that unaccredited individuals are using bedside sonography to determine management of acutely unwell patients. As junior trainees are rarely expected to be sole ‘decision makers’, the supported environment offered in core training is ideal for acquisition of USS skills which are likely to be invaluable as they progress through their career. The ability to record images enables scans to be easily reviewed by senior colleagues and management plans to be approved. I have benefited from very supportive supervisors who have facilitated this approach allowing me to utilise ultrasound in these acute environments.

Provided a ‘rule-in’ rather than ‘rule-out’ philosophy is embraced, scanning by trainees may still provide valuable information to guide management. POCUS teaches trainees to identify particular findings which, whilst not highly specific, provide important additional clues for diagnosis. On numerous occasions, I believe this information to have expedited diagnosis and refined the management of acutely unwell patients as illustrated in the following case.

A 30-year-old male, with a background of severe learning disability and recent viral illness, was admitted during the night to our Acute Medical Unit with a two-week history of peripheral and testicular swelling. The Emergency Department had initially sought a surgical review during which there were deemed to be no acute surgical concerns. Further examination by the medical team revealed a raised jugular venous pressure, increased shortness of breath on exertion and bi-basal coarse crackles with significant cardiomegaly on chest X-ray.

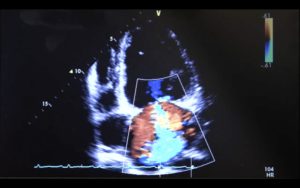

I performed bedside echocardiography to investigate for any pericardial effusion or tamponade. The patient was noted to have severely impaired left and right ventricular function (<15%) with biventricular dilatation. No evidence of pericardial effusion. The images were saved and reviewed by the Cardiology Registrar during the post-take ward round with a suspected diagnosis of viral cardiomyopathy. The patient received no further imaging and was discharged with new medication and a plan for outpatient investigation with departmental echocardiography.

POCUS is gaining favour within frontline specialties for its ability to provide prompt valuable clinical information at the bedside. This case demonstrates the potential benefit for diagnosis, management and length of stay provided a ‘rule-in’ philosophy is adhered to. In the future, as accessibility to ultrasound machines increases and practical skills develop, the capability of individuals to identify pathology at the bedside is likely to improve. Furthermore, this training is likely to become a mandatory requirement to progress in specialties such as Critical Care and the new pathways deliver a structured approach to learning allowing development of skills in a supervised environment. It is feasible that accreditation may be achieved within the initial years of core specialty training and, as an example of this, I would encourage all trainees to embark on developing and accrediting in this fundamental skill. This will ultimately enable the clinician to diagnose promptly, not only improving quality of care, but most importantly improving patient journey.